Messy-Middle – The mysterious place of consumer decision-making

Authors: Juergen Roesger & Aaron Herbst

Many long for the good old days: simple linear processes from mass product awareness to purchase. Even though in the 90s Gerd Gerken's "Farewell to Marketing" gave the first theoretical warnings that things would soon become quite different, namely dramatically more complex, it ultimately took another quarter of a century and a new everyday medium for mass individualization to become the standard.

Today, as soon as we consider buying a simple white T-shirt, a flood of information and choices hits us. We find dozens of articles online about the perfect t-shirt, content from fashion influencers offering "advice" and rankings, brands trying to convince us of their products, online retailers enticing us with discounts and coupons, online fashion magazines making recommendations, and so on. Welcome to the Mid-Funnel!

Potential San Francisco travelers invest about 350 information and communication interactions in completing a travel/flight booking; around 80 to select a laundry detergent. Since 2015, the number of consumers who engage more deeply with their product decision in the so-called mid-funnel has increased by more than 250%. And the trend is still rising. What's the reason for this? Does everyone have too much time?

What exactly happens in the mid-funnel?

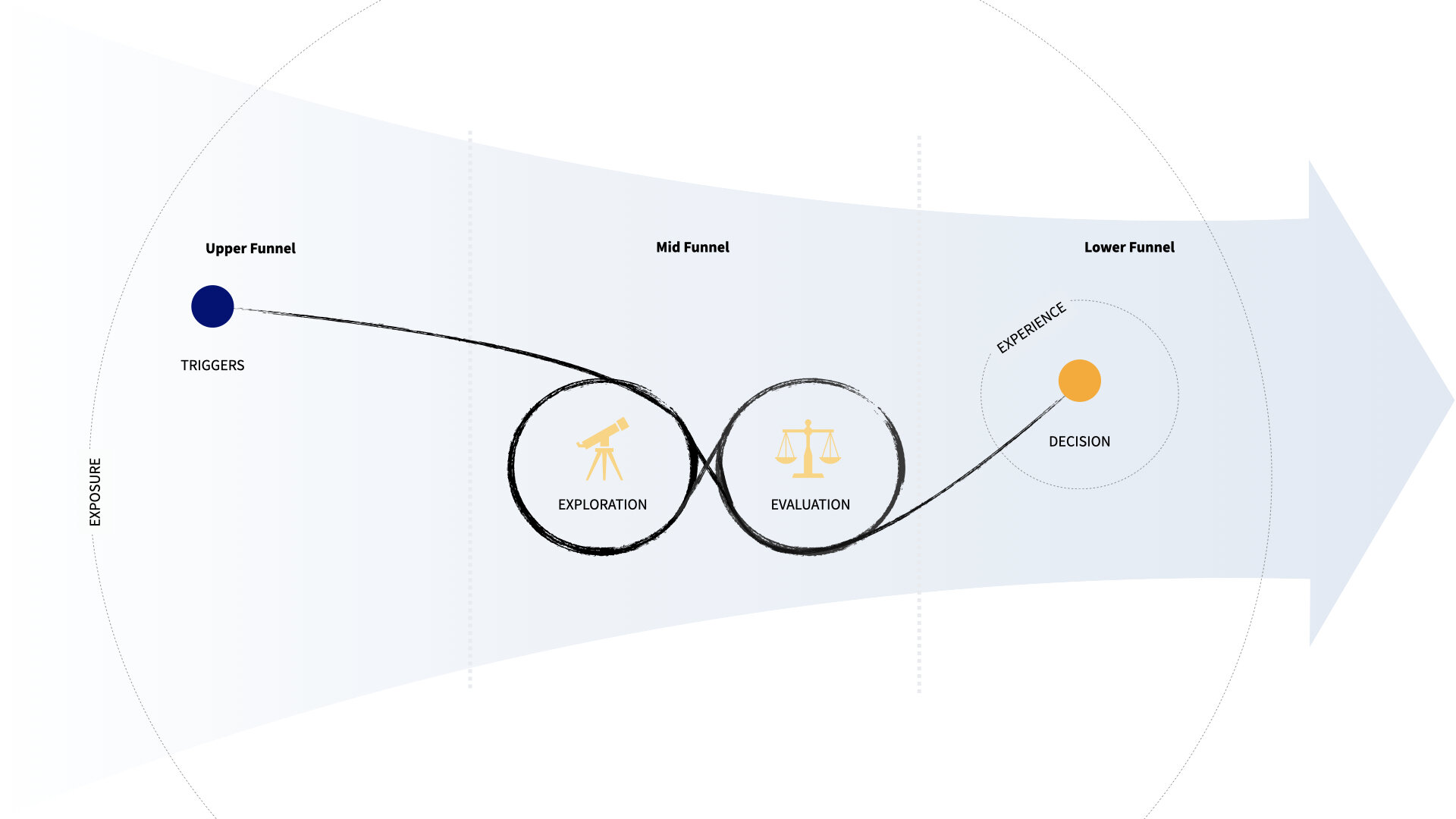

In a nutshell, the mid-funnel is the place where the bridge is built from a superficial brand / product appeal to the actual purchase of a product or service.

Let's go back to the example with choosing a white t-shirt. Depending on our previous exposure (i.e., for example, we might already have an absolutely standard white t-shirt brand that supplies us by subscription), we respond to a trigger (such as looking in the closet in the morning) and start a search process. Once we start searching online, we get numerous messages and information from brands, online retailers, influencers, fashion magazines, review portals, etc.... In the mid-funnel, we explore these opportunities and evaluate whether they suit us. In doing so, we distinguish between the more emotionally driven and the rational evaluation. Potential customers jump back and forth between these two phases until they finally make a purchase decision. After the purchase, when the actual experience begins, firms have the opportunity to influence subsequent purchase processes by proving their product and experience quality and set triggers for up- and cross-selling (see also: Impact of Experience on Brand).

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

What are the underlying motives?

Support in consolidating information

The prospective customer has a specific purchase interest, need or question for which he seeks in-depth offers, contents, and experiences also from others.

Showing options and opportunities

Through the various content-related impulses, the interested customer seeks and receives ever more new insights. Through these "moments of research", the decision priorities can be ordered, and the exploration and evaluation process initiated again and again. The perceived certainty of the decision increases.

Weighting of content – „Digital sales pitch“

In a permanent sequence of tradeoffs between emotional and factual arguments on topics such as price/performance, social perception and affiliation, future security or sustainability, something like a "digital sales pitch" evolves between the prospective customer and the supplier.

Decision preparation

The consumer's final attempt to reach a purchase decision based on the emotional and factual impulses.

Abb.: Google Australia, 2020

What are the underlying mechanisms?

Actually, it’s quite simple. The decision-making process constantly swings back and forth between emotional impulses and rational criteria resembling a never-ending ping-pong between the right and left hemispheres of the brain, between emotion and rationality. And this is all about the ultimate assessment of issues such as:

Social perception of products/services

What will my friends say about the purchase?

Is the price-performance ratio right?

How do I feel about the product?

Is it future-proof?

How will my community perceive me after the purchase?

and so on…

What does this mean from a quantitative perspective – what are consumers searching for?

Importantly, permanently emerging new „moments of research“ influence the decision criteria during the purchase decision process.

This means that new research impulses constantly influence the decision-making process. Based on 250,000 respondents who were about to make a purchase decision, Google Australia conducted one of the largest studies on this topic and came up with very impressive results.

On average, around 300 different decision-making and behavioral principles (some of which are deeply psychological) influence a consumer. Through very elaborate research, Google has categorized them into 7 core principles. We have examined them in detail and also compiled certain solution approaches.

The 7 behavioral principles (source: Google AUNZ) in the mid-funnel and possible solutions

Overarching brand presence

The brand or product should be visible in the category context and in the context of all possible use cases.

Consumers are not necessarily looking for specific products or brands, but increasingly for solutions to their use cases. In the case of a car purchase, these can include safety, horseback riding, having a good overview, going on a weekend trip with a kayak etc. During this use case exploration process, it is crucial for the brand to be visible to the consumer and serve as a use case solution. This means, in turn, that firms must understand the context of the planned car purchase. To this end, I as a supplier should analyze which potential use cases exist and are relevant from the customer's point of view, and how I can best cater for them. Classic automotive KPIs are no longer enough; instead, it is increasingly necessary to develop and provide comprehensive, use case-tailored relevance and content strategies.

In this regard, methodological tools such as relevance analysis help to identify contextual connections between the product or brand and consumers’ use cases. Based on the findings and data, suitable content strategies can be derived, implemented, and optimized.

Category heuristics

Short descriptions with core features that are relevant to category users simplify the benchmark.

CO2 emissions, organic labels, quality certifications and other categorization features such as test results or the membership in a hotel alliance (e.g., Relais & Chateaux) help consumers better classify products and services.

Considering the hotel example: In order to be prepared for different consumer interests, the hotel should become a member of Relais & Chateaux (or something similar), tackle the sustainability issue with green energy or particularly efficient energy consumption, use only regional products in the kitchen etc. This should be communicated to the respective target groups and be visible in the mid-funnel.

„Power of now“

The longer one has to wait for a product / solution, the weaker is the perceived added value.

Availability is therefore an important decision trigger and accelerator, especially in combination with scarcity messages (e.g., “only 3 rooms are left in this category”) or guaranteed availability (e.g., “order by 6 pm and the product will be delivered at the latest the day after tomorrow”).

Social proof

Recommendations and reviews from real users are particularly convincing – even if they are not only positive.

Consumers adapt their opinions and usually follow the behavior of their social community (see also: Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). A good example is the willingness to wait 45 minutes in the cold for a seat in a trendy burger place, while avoiding a half-empty restaurant with comparable quality on the opposite side of the street.

A possible solution is the adaptation of the brand benefits or use case benefits as well as the USP specifications to different social segments (for one customer X and for the other Y is the reason to choose a certain brand).

Scarcity bias

The lower the stock or availability, the more tempting is the product.

The game that Booking.com & Co have mastered perfectly is that of scarcity in order to accelerate decision-making processes. Basically, for consumers it's about competition with other interested buyers for a rare (socially consumed) good (e.g., It-bags, sneaker editions...), which touches individuals’ vanity.

Authority Bias

An expert or opinion leader is particularly convincing.

A purchase recommendation from a proven expert or a confession that he or she uses the product has a high impact on purchasing decisions. Think for example of product-testimonials or entire product lines such as Jamie Oliver Tefal pans. The basic trust in expert authorities is also one of the drivers of social norms.

Another form of authority bias is winning or scoring adequately in a comparative or produc test, which is again closely related to the topic of category heuristics.

„Power of Free“

A gift for a purchase is an irrationally strong motivator – even if it is unrelated to the product.

Consumers have a very high affinity for anything that is offered for free, be it free shipping by Amazon when buying the second book, free breakfast, 20% more content for free or an additional shopping voucher. “Free” is extremely effective (see also: Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational). Various experiments have shown that it is not always about pure added value, but quite often about simply getting something for free on top (https://www.neurosciencemarketing.com/blog/articles/the-power-of-free.htm).

How do providers exploit this phenomenon and use it to increase their added value? Take the example of “free breakfast”: It can mean that you get the standard breakfast for free, but all the extras such as egg dishes, orange juice, and cappuccino have to be paid for. Especially in countries like the U.S. and Australia this is a good way to attract guests to the hotel and increase their CLV. At the same time, for free is also very powerful in accelerating the purchase decision process in the long run, especially when it comes to time or quantity limitations (scarcity bias; e.g., “currently 27 other people are looking at the room”, “only 3 places are available”...).

Effects of the 7 principles on the purchase decision process – a short excursion into Google’s market research study

This experiment was about how and in which combination the 7 principles defined above have an impact.

Around 31,000 consumers were presented with their 1st and 2nd choice brands for various product categories in a uniform grid.

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

The mere exposure to the choice options makes on average 30% of the respondents prefer their 2nd choice brand (see Figure below).

Abb.: Google Australia, 2020

When the 2nd choice presentation is loaded with content that serves the identified principles, the majority of consumers switch (see Figure below).

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

This finding is more than impressive, but it gets even better.

Test 2: Does this also work without a well-known brand?

In this study, the 2nd choice brands were replaced by fictitious brands with which the respondents had never interacted before.

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

As the figure below demonstrates, the effect of the 7 principles was also confirmed in this experiment.

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

Simply because a fictitious brand is able to better serve the experience-, convenience-, and bias-driven heuristics in the decision context, a brand image that has often been cultivated for decades is no longer sufficient on its own to be able to win this decision process.

Google has developed an action model based on these insights.

Fig.: Google Australia, 2020

The basis for sustainably convincing consumers is to identify relevance and intelligently linking it to suitable content and offers based on data.

Viewed in isolation, the fields of action are nothing new. The decisive difference is the data-driven and thus customizable orchestration in the mid-funnel. The target group- and situation-specific deployment and combination of the 6 fields of action is an extremely powerful marketing tool. With real-time competitive analysis tools, brands are even better able to understand in which context a potential buyer should experience the product in order to react to it as positively as possible and thus to optimize their offers in a context-relevant way.

Conclusion: It is both demanding and challenging to successfully and sustainably manage the mid-funnel...

The mid-funnel makes the interaction of brand actions and performance measures difficult to control, such that focused actions must be taken to not lose customers on their way to a purchase.

Brands therefore have to find new ways to win customers in the crucial mid-funnel area. This is where the purchase decision is made and also where the competition, price comparison sites, influencers, etc. lurk to convince the customer.

The Mid-Funnel is the connect- and performance-link between brand awareness building and lower-funnel conversion.